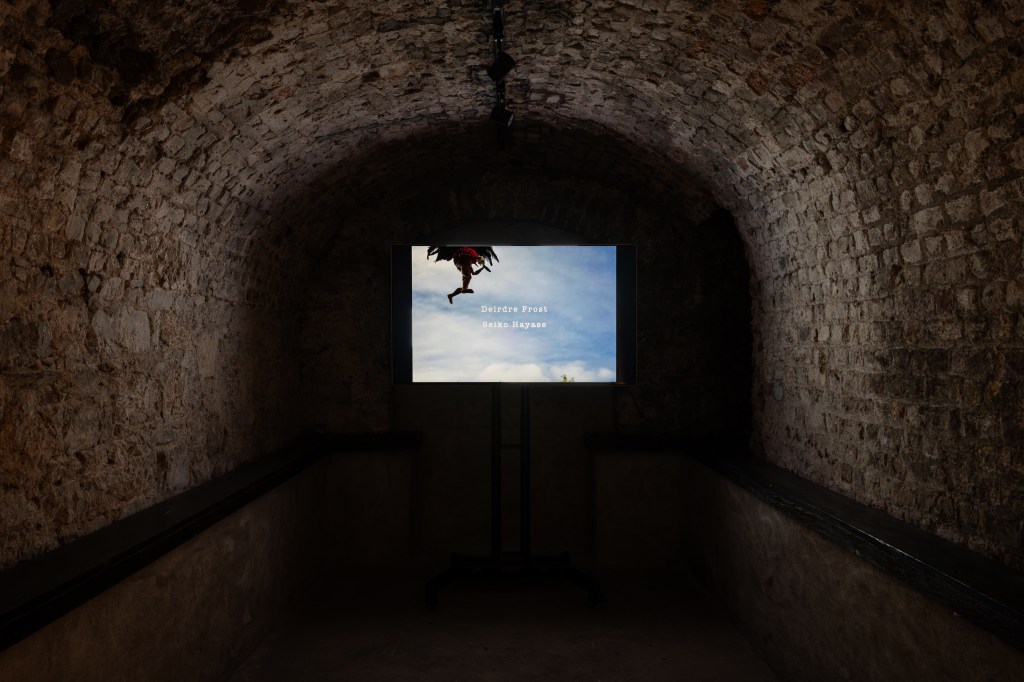

2-person exhibition at Lavit Gallery, Cork with Seiko Hayase

文明開花 means ‘civilisation’ in Japanese, and is written using characters that mean ‘blooming culture’. ‘Bloom’ can be considered a positive, when something has flowered, is in it’s prime or at it’s peak. However an algal bloom for example can be considered a negative event, a sign of ecological imbalance. Looking at the idea of peak humanity in this Anthropocene age, with the potential collapse of multiple organisational systems looming globally, the artists consider the idea of civilisation blooming.

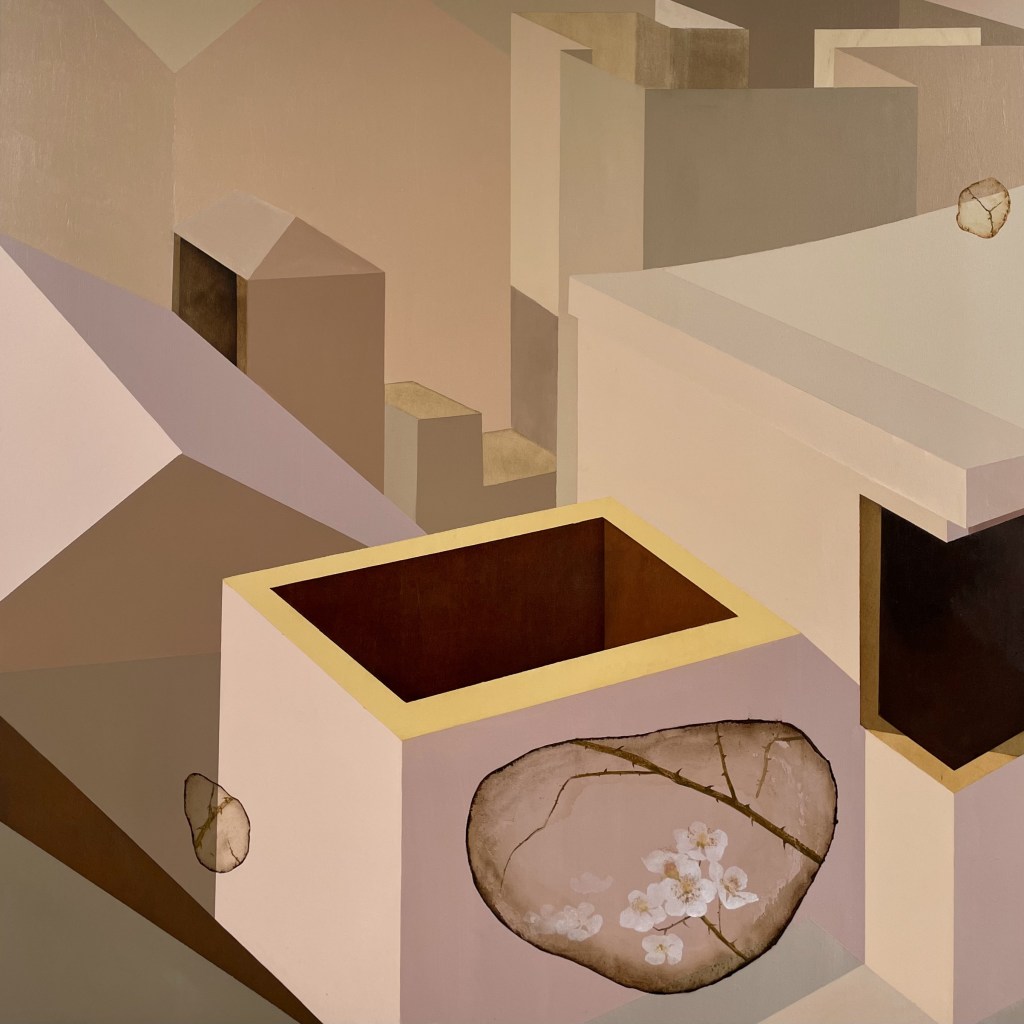

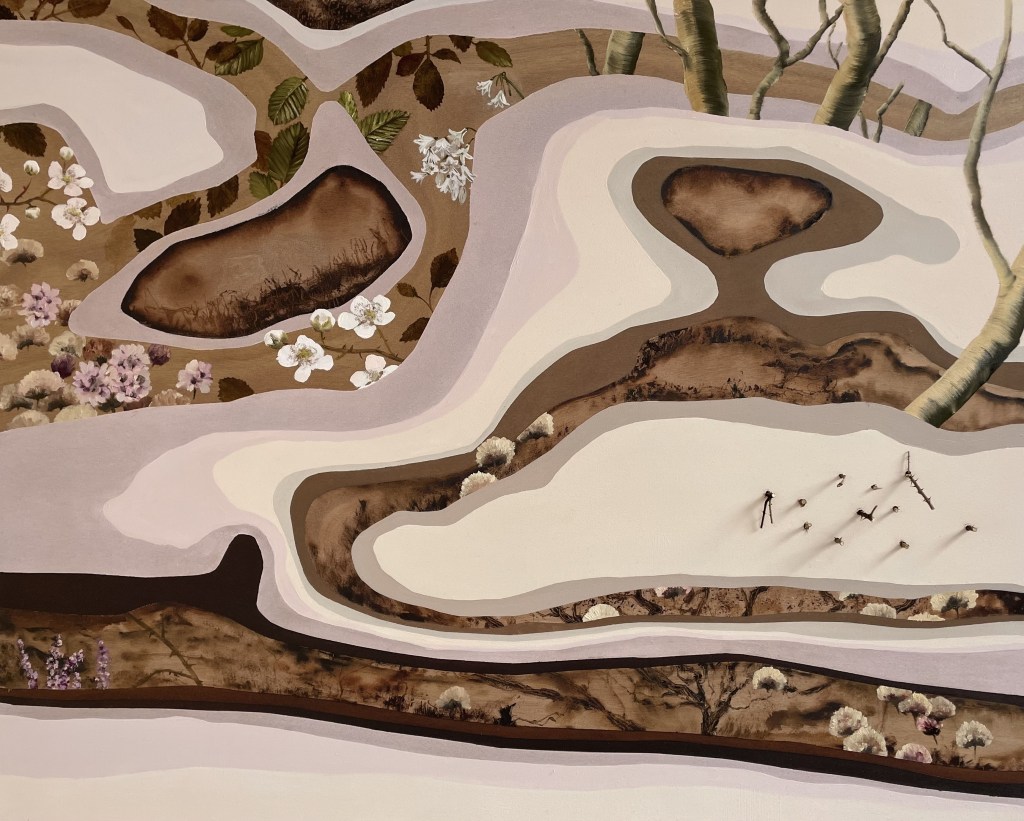

Deirdre Frost, Aiteas Aitinne, 2024, oil on panel, 93 x 122 cm

Deirdre Frost, Bramble Bloom, 2024, oil acrylic and sand on panel, 61 x 97 cm

Deirdre Frost, The Split, 2024, oil, acrylic and sand on panel. 61 x 107 cm

Deirdre Frost, Tumbled, 2024, oil, sand and plaster on panel, 61 x 61 cm

Deirdre Frost, Soft Slumber, 2024, oil on panel, 122 x 122 cm

Deirdre Frost, Fásra, 2024, oil and brambles on panel, 80 x 100 cm

Deirdre Frost, The Charge, 2024, oil on panel, 40 x 34 cm

Deirdre Frost, A Breeze Blows, oil on panel, 40 x 34 cm

City Flora Trio

Cothaíocht (nourishment), 2024, oil on ceramic on French walnut base

Taighde (research), 2024, oil on ceramic on French walnut base

Spraoi (play), 2024, oil on ceramic on French walnut base

Excerpt from exhibition text by writer and artist Sarah Long:

‘This attention to the parabolic uses of plant life can […] be seen in Deirdre Frost’s work. Her three large vases, titled Cothaíocht (nourishment), Spraoi (play) and Taighde (research), contain depictions of lush foliage, flourishing verdure and fruit associated with these terms. Frost’s experimentation with pottery is a new venture. These vases were made at Louis Mulcahy Pottery in the poignantly declining Gaeltacht area Ballyferriter in Co. Kerry, where Frost spent her childhood summers. The influence of poet, potter, gaelgor and family friend, Louis Mulcahy and his writings on the craftsmanship of ancient civilisations can be seen in the work. Frost’s pottery evokes antiquity and suggests an atavistic desire to represent plantlife. Unlike traditional designs, however, the vases are broken, and the painting occupies the ceramic interior. The vases, devoid of their function as vessels, act as ruins of the classical era, reminding us of previous civilisations’ collapse.

Frost is particularly interested in using floral imagery to explore seed and plant exchange’s role in the emergence of globalism. In the late 15th Century, Europeans sought spices influencing the Portuguese, Italian and Spanish to explore other continents, while sugar cane and the labour involved in its cultivation led to the trans-Atlantic slave trade that shaped the modern Caribbean and beyond. In Ireland, the potato and its limited genetic base and pest problems, exacerbated by colonial exploitation of the land and its people, resulted in The Great Famine (1845-1852) and mass migration. Remarkably, Frost’s research uncovered a botanical garden established in Cork University College during this catastrophic event, as well as a botanic garden established before this in Ballyphehane in 1803. Taighde, the vase illustrating research, includes hands wearing green gloves amongst painterly renderings of medicinal plants. The context under which research has been and continues to be undertaken is fraught with power dynamics between colonists and the colonised, capitalist or state interest versus impartial or community interest and between humans and nature. This conflict is insinuated by the ghostly hands that appear to be stealing fruit.

Frost’s vase, Spraoi, incorporates daisies, horse chestnuts, and ribwort, potentially evoking a less extractivist curiosity towards nature. An image of a child playing amongst flowers associated with childhood games such as daisy chain making, conkers and soldiers suggests an almost prelapsarian harmony. Likewise, the vase depicting edible vegetation seems to signal a quaint wish to simplify our relations with our environs. Frost recalls how a community of people would beseech her grandparents for a sprig of thyme from their garden. A cutting from this plant, grown by her grandmother in the 1950s, continues to be used in her family’s cooking today.’